Go back

Warning: the creeping takeover of Open Science

10/11/2021

“The shift in the pattern of land ownership caught us largely unawares in the last century”.

Roly Smith (from notes by Henry Folkard of BMC and Terry Howard of RA and SCAM)

following the 1932 mass trespass against the restricted access to Peak District moorland (Hayfield Kinder Trespass Group)

The cOAlition S Rights Retention Strategy (RRS) was designed to provide researchers with the opportunity to submit their manuscript to any research journal they choose whilst remaining compliant with Plan S. As such, it was developed with the aim of empowering researchers to be able to use their own author accepted manuscripts (AAMs) as they choose, without having restrictive third party terms of use imposed on them. At the stage when the article is accepted by the editor for publication, after the author has made changes as a result of peer review, the content of the article is the intellectual property of the author. The RRS is currently directed towards research articles published in academic journals – a Plan S high priority.

Rights retention is an author’s fundamental right. Of course, a publisher has added value to the publishing process at the acceptance stage. The publisher administers the peer review process or puts a submission system at the disposal of authors, reviewers and editors. However, by imposing restrictive terms on the use of the content of the AAM, the publisher is making a rights grab, claiming rights that were never theirs. Author rights in exchange for the use of a submission system does not make a fair trade. Certainly, the use of the submission system should be paid for, but these costs should be recouped via the subscription or the APC for the VoR.

Unfortunately, author rights retention has become inextricably associated with models of publishing journal articles in subscription journals. It shouldn’t matter if it’s a ‘green’, ‘gold’ or ‘sky-blue-pink-with-yellow-spots’ publishing model. Rights retention and publishing models should be mutually exclusive, and rights retention should not be a factor deciding where an author chooses to publish. That publishers are making it this way – by adding contractual terms to stop an author sharing their manuscript when the work is destined for publication in a subscription journal – is disingenuous to their authors and to scientific discourse. Springer Nature has even weaponised the use of RRS i) by employing a ‘green’ versus ‘gold’ publication model argument, and thereby a ‘reason’ why funds should be made available to ‘invest in gold OA’, and ii) to imply funders want to use it for ‘free’ publishing. This is nonsense as cOAlition S funders are committing millions towards payment for publishing services (see, for example, UKRI which “will provide increased funding of up to £46.7 million per annum to support the implementation of the policy”).

Looking beyond the article

cOAlition S views the adoption of its RRS as critical for ensuring that articles published behind a paywall can be made available Open Access.

Indeed the RRS offers an opportunity for subscription journals to publish material which, in order to be available open-access, would otherwise have to be submitted to a different journal. More importantly, though, the RRS asserts a fundamental principle: authors should retain sufficient intellectual property rights on their work. This is especially important as different publication types – e.g. pre-prints, micro-publications, recordings, working papers, methods etc.– emerge under the auspices of Open Science.

Put simply, authors should be empowered to retain their rights for all output types, now and in the future, so that author rights retention becomes the norm.

All researchers and those working in the field of scholarly communications are mindful that scholarly research dissemination is evolving rapidly. For many disciplines, the ‘article’ is no longer the sole primary vehicle for disseminating research findings. Research outputs are becoming increasingly diverse, and findings are presented, so they are open to scrutiny throughout all phases of the research process, rather than just towards the end. For example, researchers are disseminating their research methods and protocols to assist reproducibility and for comment to improve research quality. Open Access is no longer the be-all and end-all of openness: dissemination now encompasses broader Open Science. This is perhaps best illustrated by the notable rise in the popularity of preprints, which are increasingly being recognised as important research dissemination objects in their own right, the first step in a ‘Record of Versions’.

The case of preprints

Preprint servers across many disciplines have been blossoming since the launch (in early 1990s) and rapid growth of the high energy physics preprint server, arXiv. Many researchers use preprint servers that are independent of the major legacy publishers. According to the ASAPbio list of 56 preprint servers, 39 out of 56 are today owned by academic institutions, funding organisations, charities, individuals or community-owned, non-profit organisations, research infrastructure programs, or societies. This list includes well-known services such as those provided by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory such as bioRxiv and medRxiv.

However, in recent years major publishers have set their sights on owning services that support multiple phases along the research process, including preprint servers. Examples include:

The consolidation, market dominance and control that such major publishers have over the journal articles landscape is well documented (see here for example). There is a risk that the same could be extended, indeed is being extended, to preprint services. See images below.

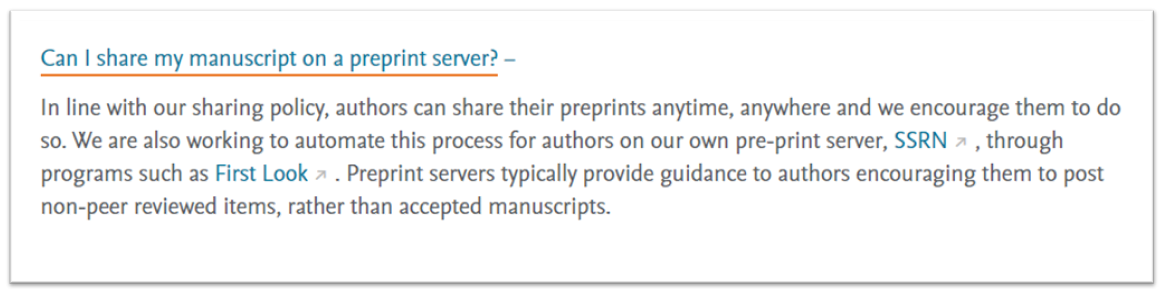

Elsevier Sharing policy

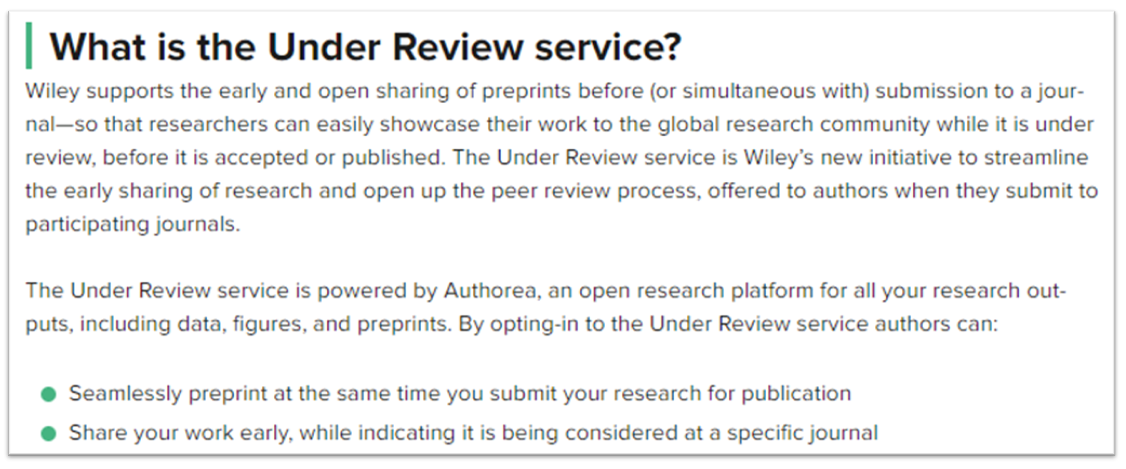

Wiley Authorea preprint service

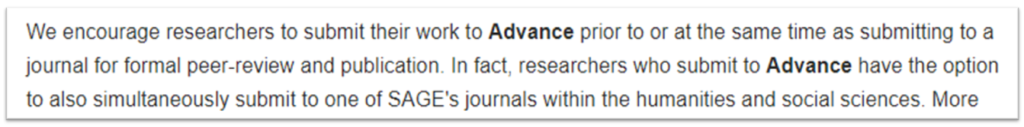

Sage Advance preprint server

Commercial publishers owning preprint services control the content deposited in these services. Preprints could be seamlessly integrated into their full suite of services, providing full service – and maintaining full control – from preprint to peer-reviewed publication. Subsequently, publishers could move to require authors to use these services, changing their terms and conditions to restrict the rights ownership and permissions of preprints deposited in their servers. Needless to say, such a scenario would negatively affect the use of community-owned preprint services, increasing the dominance of a handful of major players over the entire research process from inception to publication.

Some major publishers are already making a grab for authors’ rights for articles. They could do that for preprints as well, and if for preprints, then, as they provide additional services for other ‘early publications,’ they could do it for any research output item they hold.

The quotation about land ownership at the opening of this blog was used for good reason. Major publishers’ control and ownership of research publication and dissemination services and their content can, and is, creeping up on the research community. As one means towards retaining the freedom to use their own work as they choose, researchers would be well advised to get into the habit of retaining their rights.

Sally Rumsey

Sally Rumsey was, until July 2022, Jisc’s OA Expert working as support for cOAlition S in all areas covered by Plan S, especially the Plan S Rights Retention Strategy. Prior to that, she was Head of Scholarly Communications & RDM, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. There she managed the University’s repository service for research outputs, Oxford University Research Archive (ORA and ORA-Data https://ora.ox.ac.uk). She was previously e-Services Librarian and manager of the repository at the London School of Economics. Sally remains a member of the UKSCL (Scholarly Communications Licence) group.

View all posts by

Sally Rumsey