In 2008 Harvard’s Faculty of Arts & Sciences voted unanimously to adopt a ground-breaking open access policy. Since then, over 70 other institutions, including other Harvard faculties, Stanford and MIT, have adopted similar policies based on the Harvard model. In Europe, such institutional policies have, so far, been slow to get off the ground.

But we are beginning to see that situation change. Over the last months, an increasing number of European institutions have started implementing their own rights retention policies, thereby ensuring that research outputs are disseminated as widely as possible, whilst their researchers retain the freedom to publish in the journal of choice.

The N8 Research Partnership is a collaboration of the eight most research-intensive Universities in the North of England: Durham, Lancaster, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Sheffield and York. Working together, all eight institutions issued a statement on Rights Retention, demonstrating their determination to support their researchers in taking control over their own work. In the following post, Professor Christopher Pressler, John Rylands University Librarian of the University of Manchester, and representative of the N8 Research Partnership, gives us a view from the ground and explains N8’s approach to Rights Retention.

Rights Retention is the next step on the journey towards a fully open access global research environment. It allows our researchers to retain copyright and Intellectual property on their work and, in so doing, place that research immediately on publication in our repositories regardless of publisher’s embargoes. Without this ability, researchers will find themselves caught between those publisher policies and many funders’, including UKRI mandates on immediate open access.

There are many challenges facing universities and, indeed, the world at this moment. Our capacity and resolve to meet those challenges through research and innovation have never been more determined. Although the great breakthroughs and discoveries in research are the aspects of our work that makes the news, the many processes and teams in the background that support this work are equally important.

The role of the Library and our research offices are a part of that infrastructure, and formal policies such as rights retention ensure that control over their ideas remains with the researchers who authored them.

The Rights Retention Statement has been fully adopted by Senate here in Manchester and is going through similar steps in our partner N8 universities. We now have a Publications Policy tailored for the 21st Century, where the purpose of our research, to improve and ensure equality in society, will be maximised by access to world-leading research for global scholarship. This initiative originated in our libraries but is very much a team effort across our faculties, research support and legal teams.

We are excited to be able to support our combined research community as they work within the new context of the UKRI OA Policy, mandating immediate Open Access to research on publication. Much research will be covered by gold OA agreements, but for those outside such licenses, the green OA route, whereby researchers can deposit their papers in institutional or discipline-specific repositories on publication, will be made possible by asserting rights already held by researchers on submission to publishers.

Although the Rights Retention Statement being adopted across all eight Northern research-intensive Universities originally began as a discussion between the N8 libraries, it is formally supported by senior leaders for research and VCs throughout the N8 Research Partnership. We believe that we are stronger when we act together and from the same position. This is the first consortia statement on this vital issue in the UK and draws on the very significant research power of the Northern research-intensive universities.

It was fitting that the symposium on the Future of Research Publishing and the launch of the N8 RRS was held at The University of Manchester’s John Rylands Library, one of the acknowledged great libraries of the world. Such a Library is representative of the role libraries play in society in terms of caring for historical knowledge in the context of influencing the future. This initiative is made possible by libraries and researchers working closely together within the vibrant context of the N8 Research Partnership and, in so doing, provides an example of leadership and collaboration in the ever-changing world of research publishing.

This is a new area of development, and although there are some documented cases of pushback from publishers to academics asserting their rights, these are rare. We assume it is because, although not historically standard academic practice, it has always been known that researchers (or indeed their institutions) hold copyright on their work and not the companies that publish it. RRS is aimed at situations where gold access is not achievable whilst at the same time green (immediate on publication) has been embargoed or directly blocked by a publisher in order to maximise sales. This situation is now in direct conflict with many funder’s policies, and the N8 RRS is designed to support researchers who find themselves caught between the two.

At Manchester, for example, we have a large team of librarians, legal advisors and researchers coordinated by The University of Manchester Office for Open Research, based in the Library who can support academic colleagues through every part of the process, including if they find their submissions rejected because they assert their legal right to deposit in green repositories.

Rights Retention is a significant step forward, not least in ensuring OA can happen on publication but also in redressing the unfortunate practice of universities giving away IP or copyright to publishers.

The Rights Retention Statement matters because the sector has struggled to initiate progress towards open access for decades. At the root of this has been the transfer of intellectual property of submitted research outputs to publishers by researchers. This once standard practice has slowed progress in open science and public access to research by at least thirty years.

The sector, it must be admitted, frequently led by university libraries, has in the past been forced to negotiate change rather than work in real partnership with publishers leading to further years of slow movement on transformative agreements where subscriptions are replaced by accepted OA charges. Without Rights Retention, the sector is still giving research IP to publishers and buying access to it in perpetuity. It is, to put it mildly, an unhelpful model, as aside from journal distribution and marketing, almost all peer review and content development are also delivered by Faculty, not publishers.

Rights Retention sits alongside long overdue mandates for immediate OA, such as the UKRI OA Policy. It is a significant step forward, not least in ensuring OA can happen on publication but also in redressing the unfortunate practice of universities giving away IP or copyright to publishers who then hold all the cards in negotiating the price to access those same universities’ content. Rights Retention means researchers will, for the first time, have a strong hand in terms of control over their own work and transforms the position university libraries often find themselves in when negotiating with suppliers who claim ownership over content produced by those same universities.

In 2008 Harvard’s Faculty of Arts & Sciences voted unanimously to adopt a ground-breaking open access policy. Since then, over 70 other institutions, including other Harvard faculties, Stanford and MIT, have adopted similar policies based on the Harvard model. In Europe, such institutional policies have, so far, been slow to get off the ground.

We are beginning to see that situation change.

The University of St Andrews has launched a new Open Access Policy, in effect from 1 February 2023, which harmonises the requirements from research funders, provides greater support to their researchers and aligns with the University’s strategy to “make their research findings widely available for local, national, and global benefit”. In the following interview, Kyle Brady, Scholarly Communications Manager at the University of St Andrews, describes the process which led to the new OA policy, highlights the benefits for the university and its researchers and shares practical tips for other institutions that might consider adopting similar policies towards making all publications openly available as quickly as possible.

cOAlition S: How did the idea of adopting an institutional OA policy emerge? Can you describe your approach at the University of St Andrews?

Kyle Brady: The University of St Andrews first introduced institutional open access requirements back in 2013. At that time, the focus was largely to support researchers to meet the Research Excellence Framework (REF) and funders’ OA requirements. We also wanted to reflect our own commitment to open access, especially Green OA, which has been embedded as a preference in our OA Policy since its inception. Those main drivers have remained in place, but the landscape has changed a lot in 10 years, so we needed to ensure we could support researchers in the new OA environment – where researchers are increasingly required to retain rights and where monographs and chapters are also expected to be OA.

Therefore, St Andrews’ new open access policy states that all St Andrews researchers must deposit their accepted manuscripts in the university’s research information system Pure, to be made available via the University repository with a CC BY licence and zero embargo. Researchers are further required to include a ‘Rights Retention’ statement on submissions to ensure they retain rights to reuse their manuscript in alignment with the policy. We also included requirements for monographs and chapters, where there is a research funder mandate for open access to these output types. Currently, this applies to Wellcome Trust and Horizon Europe, and will include UKRI-funded monographs and chapters from January 2024. Once the next UK REF requirements are announced, we are well-positioned to extend the scope of our monographs and chapters policy, meaning it will apply broadly across all researchers.

The OA policy was developed in two main phases. Firstly, we wanted to ensure the new requirements had a strong and enduring foundation within the University’s Intellectual Property policy. The University’s IP policy was amended in 2021 and now sets out the principle of retained author rights, aiming to rebalance ownership and rights in scholarly works to enable wider dissemination and reuse. The second phase was to develop a revised OA policy with the practical processes and details required for researchers to apply these rights, fully supported by their institution.

cOAlition S: What are the advantages of adopting the policy for your researchers and your institution? What did you hope to achieve?

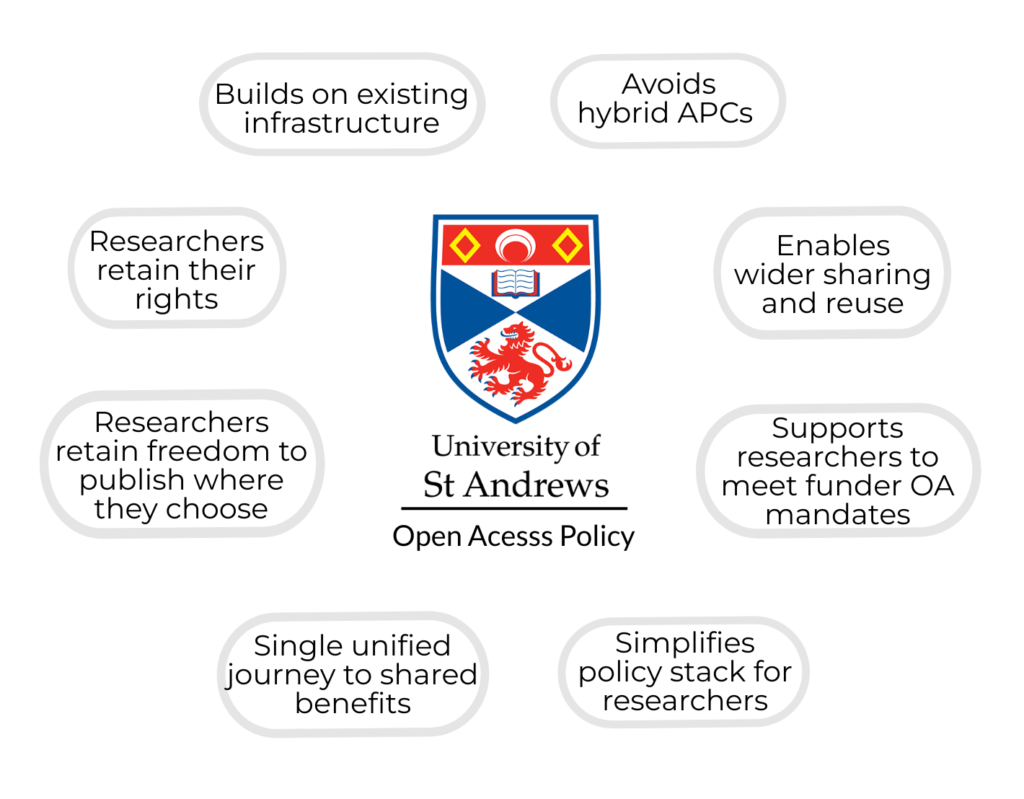

Kyle Brady: I’ve included below a handy graphic that summarises some of the key advantages of our new OA policy:

Figure 1. Key advantages of the new St Andrews OA policy

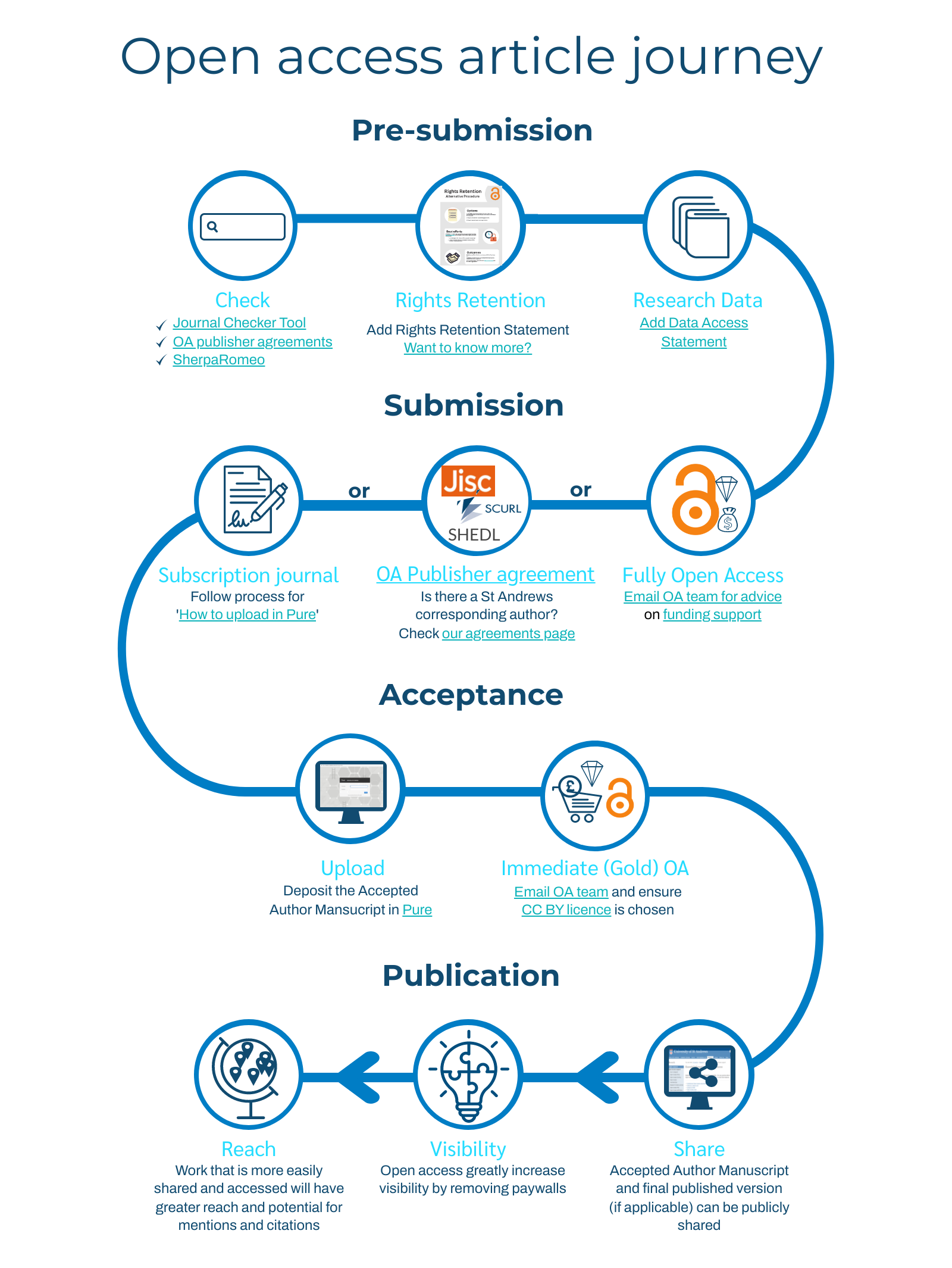

We also made a great effort to ensure that our goals were transparent. We wanted to make sure our researchers were fully supported, so if, for instance, a publisher were to push back on areas of Rights Retention and research funders’ support fell short, our researchers would feel reassured that there is institutional support available. Following this, the secondary goal was to bridge gaps and creates a shared journey (see fig 2), for instance, between STEM disciplines (where there may be proportionally higher levels of UKRI and Wellcome Trust supported researchers) and AHSS (where there may be fewer researchers with research funding that includes an Open Access mandate). With a common journey for our researchers, we can provide better advice and support, reducing the advocacy and training burden for the Open Research team while at the same time simplifying the ‘policy stack’ for researchers.

We wanted to make sure our researchers were fully supported, so if, for instance, a publisher were to push back on areas of Rights Retention and research funders’ support fell short, our researchers would feel reassured that there is institutional support available.

Figure 2. Demonstrating the unified user journey

cOAlition S: How was the agreement reached across the institution?

Kyle Brady: From the outset, we were committed to gathering feedback from across the University to ensure that the new requirements were inclusive of multiple points of view and reflective of concerns. It needed to be a collaborative project to bring our community along with us. Therefore, the University of St Andrews’ academic community was consulted widely during 2022, and that feedback was incorporated in the final draft and fed into frequently asked questions. The most common feedback was for clarification and guidance within the policy, so the document became quite detailed. The feedback also led to the development of our Rights Retention webpage, where we guide researchers through the process of retaining their rights when publishing. We also collaborated with legal and copyright experts and external colleagues, ensuring we learned from our peers and that our path aligned with other UK HEIs generally – specifically, we were thankful to the University of Edinburgh for their advice while developing our policy.

Looking back over the 12 months or so of development, there was very little disagreement about the big picture. There were many valid concerns raised, of course, but by and large, the academic community was behind the changes, and we all shared the same overall vision for the direction of Open Research at the University.

cOAlition S: In conclusion, what are your three top tips for any other university considering adopting a similar permissions-based Open Access policy to yours?

Kyle Brady: A further reflection, and something I have discovered over the years, is that when embedding change like this, we must respect that most researchers’ time and resources are very limited. This means when ‘on-boarding’, we focus on the practicalities and immediate benefits for the individual and always ensure we are reducing their admin to a minimum.

If I had to choose three top tips from our experience, it would be these, in no particular order:

- Collaborate with your communities – inside and outside your institution

- Build-in flexibility so that the policy can adapt to changes

- Focus on the practical benefits to individuals to build trust and bring others along with you.

In 2008 Harvard’s Faculty of Arts & Sciences voted unanimously to adopt a ground-breaking open access policy. Since then, over 70 other institutions, including other Harvard faculties, Stanford and MIT, have adopted similar policies based on the Harvard model. In Europe, such institutional policies have, so far, been slow to get off the ground.

We are beginning to see that situation change.

The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) is introducing its own Rights Retention Strategy, in effect from 1 October 2022, which ensures Open Access to all new scientific articles published by NTNU’s researchers from day one. In the following interview, NTNU’s Library Director Sigurd Eriksson describes the new scheme, highlights the benefits for NTNU researchers and shares his tips on how other universities can adopt similar policies towards making all publications openly available as quickly as possible.

cOAlition S: Could you please, describe the author copyright policy you have adopted at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology?

Sigurd Eriksson: With a Rights Retention Strategy, we ensure that our researchers can publish their work wherever they want while maintaining their rights to use and distribute their work. As part of our Policy for Open Science, researchers at NTNU must archive their scientific work in our institutional repository, NTNU Open, through the national research information system, CRIStin. For articles that are not published gold OA, authors must deposit the Author Accepted Manuscript (green OA) under a CC BY license. By implementing a Rights Retention Strategy, their work will be made openly available immediately after publishing, regardless of the embargo period for self-archiving often imposed through the publisher’s license agreement. With a rights retention policy and open access through our institutional repository, NTNU takes legal responsibility for its authors’ copyrights.

By implementing a Rights Retention Strategy, their work will be made openly available immediately after publishing, regardless of the embargo period for self-archiving often imposed through the publisher’s license agreement. With a rights retention policy and open access through our institutional repository, NTNU takes legal responsibility for its authors’ copyrights.

cOAlition S: Why did the idea of adopting an institutional OA/copyright policy emerge?

Sigurd Eriksson: We were first inspired by the Rights Retention Strategy developed by cOAlition S. It is our policy to make all scientific articles from NTNU openly available, yet in the past three years about 25% were still neither gold OA nor deposited (green OA). Also, articles must be deposited in a local or national repository to be included in the performance-based financing of the institution.

We believe many researchers are reluctant to deposit in our institutional repository (green OA), likely out of fear of violating any license agreements signed with the publisher, often imposing a 12–24-month embargo period for self-archiving. Publications in hybrid journals are no longer financially supported by cOAlition S funders. We realized that a rights retention policy could be a leverage in our negotiations with publishers offering read-and-publish or “transformative” agreements, as well as a motivator for our researchers to upload their peer-reviewed manuscripts in our institutional repository.

cOAlition S: How was the agreement reached across the institution?

Sigurd Eriksson: In 2021, our Library Director sent briefings about the Rights Retention Strategy to the University Research Committee, which included members of all faculties of NTNU. In spring 2022, the suggested strategy was processed by the Library Council, then send back to the Research Committee and, finally, to the rector for approval.

cOAlition S: What challenges had to be overcome before it was agreed to adopt the policy?

Sigurd Eriksson: The rector and rector’s management team wanted a broad anchoring in the professional environments at NTNU. We obtained support by allowing the case to mature over time and by gathering experience from other institutions. Establishing a dialogue with the University in Tromsø, who were the first in Norway to implement a rights retention strategy on 1.01.2022, was especially helpful.

cOAlition S: What are the advantages of adopting the policy for your researchers and your institution?

Sigurd Eriksson: Our researchers can publish wherever they want, maintain the ownership of their work, and are no longer bound by an embargo period before they themselves can grant open access to their accepted manuscripts after publishing. Our researchers do not have to inform the publisher and can be at ease as NTNU will take legal responsibility.

Our researchers can publish wherever they want, maintain the ownership of their work, and are no longer bound by an embargo period before they themselves can grant open access to their accepted manuscripts after publishing.

cOAlition S: In conclusion, what are your three top tips for any other university considering adopting a similar permissions-based Open Access policy to yours?

Sigurd Eriksson:

1. Contact other institutions that have adopted a rights retention policy advice. They are likely happy to share their experience, knowing that others will follow their example.

2. Make it as easy as possible for the researchers to follow the policy by having the institution take care of the administrative work towards publishers.

3. Be extra thoughtful of how you formulate information about the rights retention policy on your intranet. A list of questions and answers (FAQ) can be very helpful for authors.

Recommended reading

- Policy for Open Science at NTNU

- Self-archiving and Rights Retention Strategy

- Rights Retention Strategy for research articles

In 2008 Harvard’s Faculty of Arts & Sciences voted unanimously to adopt a ground-breaking open access policy. Since then, over 70 other institutions, including other Harvard faculties, Stanford and MIT, have adopted similar policies based on the Harvard model. In Europe such institutional policies have, so far, been slow to get off the ground.

We are beginning to see that situation change.

Sheffield Hallam University (SHU) has recently announced its new Research Publications and Copyright Policy, which will come into force on the 15th of October 2022. In the following interview, Eddy Verbaan, Head of Library Research Support at Sheffield Hallam University, explains why SHU decided to make Rights Retention a dominant driver of its new policy, how they benefited from similar institutional policies and what steps could other universities take towards the same direction.

cOAlition S: Could you please, describe the author copyright policy you have adopted at Sheffield Hallam University?

Eddy Verbaan: First, authors must include a rights retention statement in their submissions to journals and conference proceedings. This is the same statement that is required by the Wellcome Trust, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR).

Secondly, authors automatically license the university to disseminate their Author Accepted Manuscript without delay under the CC BY license via our repository. This is accomplished in our new policy by expanding on provisions already available in our staff IP policy and our student terms and conditions, which stipulate that our authors own their copyright but that they give the university a non-exclusive royalty-free licence to use their work for certain purposes. The new policy simply defines one of those purposes.

Lastly, the policy provides a mechanism for our authors to opt out of the requirements for immediacy and licensing if necessary.

cOAlition S: Where and why did the idea of adopting an institutional OA/copyright policy emerge?

Eddy Verbaan: We started exploring a rights retention policy when discussions around the UK-SCL initiative first emerged. From the outset, it was clear that rights retention is closely aligned with our university’s ambition to be the world’s leading applied university, and with our library strategic plan which includes a goal to advance open research. We already knew that Open Access is vital for the kind of university we are, as it helps us to share our research beyond academia with the people and organisations that we work with as an applied university. Making open access immediate, rather than after a delay, can play a role in increasing the reach and impact of our research.

Our local groundwork, collaboration and coalition building to advocate and prepare for rights retention reduced our dependence on the realisation of a UK-SCL. We had investigated how a UK-SCL aligned Open Access policy could be implemented, prior to the new UKRI policy, which put us in a good position to seek approval for a new institutional policy this year (2022). Watching and learning from the innovation of Edinburgh and Cambridge gave us more confidence to do so.

Making open access immediate, rather than after a delay, can play a role in increasing the reach and impact of our research.

cOAlition S: How was the agreement reached across the institution?

Eddy Verbaan: In a nutshell, we reached the agreement by working through existing governance structures and by aligning with existing strategic activity. It helped that earlier in the year we had proposed and gained approval for an Open Research position statement and that Wayne Cranton, our Dean of Research, and Nick Woolley, our Director of Library and Campus Services, were members of the UUK and JISC groups working to achieve sector level Open Access agreements with publishers.

Our primary forum was the existing Open Research Operations Group. This is a cross-university group that reports directly to our Research and Innovation Committee and which I chair as the library’s Head of Research Support. The group has representation from relevant stakeholders including the researchers, the library, research administration, and IT services. Early discussions about and support for UK-SCL first emerged in this group.

When we felt there was a strong case for action, we went to the Research and Innovation Committee to ask for support to propose a rights retention policy, which – given our work up to that point – we were able to articulate quite clearly. Support was given, and we convened a small task-and-finish group with members from the Open Research Operations Group, supplemented with colleagues from HR and legal services, whose contributions would prove to be vital. We created a risk register, explored how rights retention fits with employment contracts as well as with publishing agreements and consulted with the trade union. We also wrote a paper presenting the case for rights retention, which included a draft policy and recommendations for implementation. This was brought back to the Research and Innovation Committee who approved our proposal.

The main area of concern centred on questions of procedure and practicalities, such as informing co-authors. We were able to address these concerns by developing detailed guidance, including email templates, and through the provision of library support.

cOAlition S: What challenges had to be overcome before it was agreed to adopt the policy?

Eddy Verbaan: The main challenge was mindset, reaching a fuller and shared understanding of risk and reward, and establishing for example that there was nothing mutually exclusive between rights retention, version of record, and a healthy publishing industry.

It certainly helped that at the start of the process, we agreed on a set of design principles within which our task-and-finish group was going to work. The most important of these was that there should be as little administrative burden on our authors as possible, so as to avoid unwelcome workload and to maximise engagement with the new policy. We were confident that not only could we achieve this for rights retention, but that by actually taking this policy direction we were keeping things simple for authors.

Of course, our main challenge is yet to come. We have translated strategy to policy, which now in turn requires implementation as practice to then achieve impact. The main risk we identify here is that our authors may not feel sufficiently confident or empowered to include the rights retention statement in their submissions, or that they would not see the benefits of doing this. Our next action will be to communicate the why’s and how’s of our new policy to our university’s research community.

cOAlition S: What are the advantages of adopting the policy for your researchers and your institution?

Eddy Verbaan: We have issued a call to action ‘publish with power, retain your rights’ – a variation of the cOAlition S campaign slogan – and articulated the benefits for researchers as follows:

1. Authors achieve immediate and wide dissemination without restrictions

2. They retain more rights over their own work

3. They also retain the freedom to publish where they see fit

4. Whilst automatically complying with all external open access requirements

The first and foremost benefit for the institution is that we improve the communication of our research in line with our open research ambitions and our ambition to be the world’s leading applied University. For us, a key message is that improving the reach of research improves potential impact, in particular beyond academia. For example, a researcher in criminology may be better able to influence probation practises if their research is freely available online, preferably in the places where probation practitioners are active.

Secondly, because rights retention means that our authors will automatically comply with all external open access requirements, there is a clear benefit for the institution in satisfying our funders’ conditions for funding.

It is perhaps also a question of future-proofing. We know that the open access policy for the next national research assessment (REF) will be aligned with UKRI’s new open access policy and will therefore be based on Plan S principles. Introducing REF-compliant author behaviour now, will make sure this behaviour is already embedded by the time the new REF policy actually comes into force.

The first and foremost benefit for the institution is that we improve the communication of our research in line with our open research ambitions and our ambition to be the world’s leading applied University. Improving the reach of research improves potential impact, in particular beyond academia.

cOAlition S: In conclusion, what are your three top tips for any other university considering adopting a similar Open Access and copyright policy to yours?

Eddy Verbaan: Each institution will have its own peculiarities and unique challenges. But based on my own experience in my own institution, my top tips would be:

1. Understand risk and reward. Don’t get bogged down in what could go wrong, but be realistic about the likelihood and severity of potential issues. Perhaps you will find that the benefits outweigh the risks, as we did!

2. Learn from good practices but be confident you can do things as an institution – don’t wait for others to take the lead. Even the UK-SCL initiative would require institutions to implement the policy locally. We certainly benefited greatly from the thinking and exchange of the UK-SCL community and what we saw being developed at Edinburgh and Cambridge.

3. Foster a coalition of stakeholders willing to work together and come on a journey with you. We had already built a network of open research champions by the time we decided to go down the institutional rights retention route, and they have already proven invaluable in advocacy for rights retention.

I also have a bonus tip: keep it simple. In essence, rights retention is actually straightforward. Although many people will keep telling you this is a complex issue, it doesn’t have to be. You can still boil it down to a few key benefits that are achieved with just one simple action.

More questions about the new Research Publications and Copyright Policy at Sheffield Hallam University?

Visit the new Research Publications and Copyright Policy page or contact Eddy Verbaan.

The following interview was originally published on the Utrecht University website. Johan Rooryck, Editor-in-Chief of the academic journal Glossa and director of cOAlition S joined the second meeting of the discussion series Publishing in transition as a speaker on May 24. Publishing consultant of the university library Jeroen Sondervan interviewed him on his experiences with open access publishing.

When did you first engage with open access and why is it important for you as an academic, also considering the different roles you have in the scholarly communication system (reader, editor(-in-chief), advisory board member)?

I became actively interested in open access around 2011/2012, when Timothy Gowers launched the Elsevier boycott and the Cost of Knowledge protest against Elsevier’s expensive subscriptions and journal bundling. A number of very good reviewers informed me that they would no longer review for Lingua, the Elsevier journal I had been an editor for since 1999. This was worrisome, because without access to the right reviewers, a journal cannot maintain its peer review processes. So I started to think about alternatives. In 2011, I had also met Saskia de Vries, who at that time was director of Amsterdam University Press, and who provocatively asked me if I was not interested in flipping Lingua to open access, and what would be required to do so. That conversation led to many more contacts, including Natalia Grygierszyk, director of the Radboud University Library in Nijmegen, and we jointly decided to look into possibilities to make Lingua open access.

You were an Editor-in-Chief of Lingua, a hybrid journal at Elsevier. At some point in 2015, you made a bold step and resigned, and immediately started a new full, non-APC (diamond), open access journal. What made you decide to eventually leave Elsevier?

As I said, I had worked for Lingua since 1999. At the start, it was a simple gentleman’s agreement. I didn’t have a real contract, and just received a one-page statement that declared the number of subscriptions they had and the percentage of royalties they would give me for my editorial services. I was free to run the journal as I wanted, there was clear trust that I would serve the journal in the best interest of the linguistic community, and that the publisher would benefit from my expertise. Ten years later, I found myself having to sign a 27-page contract that stipulated among other things, that all mail I exchanged with authors was Elsevier’s property, that the list of 3,000 authors and reviewers, which I had carefully curated, was also their property. In addition, I was being pressured to hire associate editors from China, possibly because they were selling so many new subscriptions there (however this was never made explicit). At annual meetings with the journal manager from Elsevier, I felt like I was being subjected to an exam about the journal’s performance. So I increasingly felt like a prisoner, an extremely small cog in Elsevier’s knowledge machine, with very little in exchange. I did receive an honorarium, but if I divided that by the hours invested in Lingua, I would have been better off distributing newspapers or washing windows in my neighbourhood.

I increasingly felt like a prisoner, an extremely small cog in Elsevier’s knowledge machine, with very little in exchange.

Could you tell us a bit more about how that process of leaving Elsevier went?

I started by discussing the idea with my editorial team and some board members in late 2012: if I find a sustainable open access alternative to transfer the Lingua community to, will you support that move and join me? The answer was an overwhelming yes. So I went back to Saskia and Natalia, and we started exploring options. I had two very elementary conditions for the transition: I did not want Lingua to be the only journal to flip to open access, but to involve at least two to three other linguistics journals to show that this was part of a broader movement. That is why we set up Linguistics in Open Access (LingOA), a foundation for promoting open access in linguistics. We managed to convince three other journals to join us in flipping to open access: Laboratory Phonology, Italian Journal of Linguistics and Journal of Portuguese Linguistics.

And secondly, I wanted a long-term sustainable plan for the sustainability of these journals in addition to initial funding for the transition. All too often, journals are given some money to transition to open access, and when the money runs out the journal ceases to exist. Giving money at the beginning of a journal feels very virtuous to sponsors, but in fact what journals need is permanent, sustainable funding. In the case of the LingOA journals, we were able to secure both funding for the transition and a solution for long-term sustainability. The money for the transition was secured via the Association of Dutch Universities (VSNU) and the Dutch Research Council (NWO): we obtained 500,000 euros for five years to transition the four journals to open access. The long-term solution was an agreement with the Open Library of Humanities (OLH) that they would adopt the journals after the transition period of five years, and pay for the associated costs via their consortial library funding scheme. The OLH publishes a total of 29 journals in the humanities via a system where libraries contribute a relatively small sum, between 700 and 2,000 euros a year, to the OLH that support the costs of running the journals and of maintaining their Janeway submission system and platform, a truly innovative and easy to use publishing platform for journals.

Open access challenges

What were, and maybe still are, the biggest challenges of Glossa, starting immediately as a full, diamond open access journal?

I think our main challenge was how to reach the community and inform and convince them of this change. Because for the new journal to thrive, we had to convince the entire community to move to the new journal with us. A bit like abandoning your old car and buying a new one: will it be as good as the old car? Because, of course, Elsevier kept the old journal alive after we left, and managed to find replacements for us. They also completely changed the aims and scope of the journal while maintaining the old title. Apparently a title is a very flexible thing for a publisher.

And this is where the power of social media became apparent. We were able to rally the researchers belonging to the Lingua community via Facebook for instance, and mobilize them to support the move to Glossa. A few key figures in linguistics also heavily promoted the move, and they also engaged the community into a boycott of the old Lingua, which was called ‘Zombie Lingua’ for quite some time. Suddenly, many linguists refused to publish there or review for them.

I think without that social media campaign the move might not have succeeded. There really was a confluence of several elements that reinforced each other: we had institutional backing and support which allowed us to hire a lawyer to advise us on key aspects of the contracts Elsevier had with us, we had the support of the research community, and for some reason the story of the flip also attracted a lot of media attention and support from various organisations worldwide, which also helped a lot.

Another challenge was governance: what does it mean to have a journal owned and led by scholars How does that work? How do we imagine ownership in such a way that the journal cannot be bought by a commercial entity in the future? That is a process that we laid down in the Glossa Constitution, a document that specified that the Glossa title is in the hands of the community, and represents no monetary value. Recently, we were offered 300k to sell the journal title. We made that simply impossible via this Constitution, so there cannot even be a temptation. And you can easily understand why someone would want to offer 300k for a journal like ours: we publish between 120 and 150 articles a year. If a commercial publisher were to charge 2,000 euros per article, that could mean a gross income of 300k per year. Deduct costs of about 500 euros per article for production and manuscript handling, and you are left with a tidy profit of 225k.

An essential research infrastructure

What were the experiences in the first years of being an independent, self-controlled journal? What are good practices? And, in hindsight, what could have been organised better/more efficiently?

The experience was an exhilarating one. Suddenly I received emails from people in Indonesia, Africa and South-America who had previously been unable to read the journal. But on a daily basis of course, there was also a lot more work, because we had to set up a system of governance for the journal: how is the editorial team and the editorial board selected? How do we ensure continuity? I also think the help and commitment of experienced people in LingOA, like Saskia de Vries and Natalia Grygiercyk was crucial in this first phase. But it also helped that we were able to work with a professional open access publisher like Ubiquity Press, who helped us think about many questions of good practices.

Secondly, the increasing realization that a journal is in fact a community, and not just an outlet for articles owned by a commercial publisher, led us to make explicit the good practices that can be shared by other journals. We formulated author guidelines, not only in terms of what authors must do before submitting their paper, but also in terms of what they can expect from the editors and the reviewers. We formulated editorial policies and reviewer guidelines, again with the generous help from people in the community. We developed data policies, and ethics guidelines in line with COPE.

Funding is a major issue here and in the last decade or so, many journals that started as a diamond journal struggled with their long term ambitions, due to lack of sustainable funding. What do you think is needed (and let us focus here on the Dutch situation) to support diamond open access journals (and platforms) in a sustainable way?

Indeed funding is essential. Very often, diamond journals are treated like commercial startups. Various organizations are quite enthusiastic about giving some initial funding which makes them look good because it allows for considerable virtue signaling. The idea then is that the journal should be able to sustain itself after a number of years. But that is erroneous: since diamond journals typically do not charge authors or readers, they entirely depend on revenue streams from the public sector: ministries, research funders, universities and their libraries, donors etc. And that money tends to come in the form of time-limited projects that do not even ensure renewal of the money as a function of successful and sustained publication.

While in fact journals should be viewed as essential research infrastructure, in the same way as university buildings, labs, and libraries: you have to maintain infrastructure for the long run. Imagine you were to tell professors: here is a classroom, but three years from now, we expect you to be able to pay for the chairs and the tables and the blackboard and the chalk. That would be completely ridiculous, but that is how scholar-owned and scholar led journals are being treated today. Now of course we need not just throw money at journals just because they are journals: funding can be made conditional on the regular evaluation of good practices, the regularity and quality of their outputs etc. But temporary funding is no good.

What is really required is a change in perspective: journals are essential research infrastructure, and if we do not fund it, nobody will.

Focusing on the Dutch situation and Dutch diamond open access journals, I think it would be good to adopt a model like that of the OLH, that is a system where a number of libraries contribute to sustaining those journals that have a proven record of quality outputs, good governance, and good practices. This need not be limited to libraries. I also think there is a role here for the ‘landelijke onderzoekscholen’ (national research schools). These organisations already organise work at a PhD-level nationally, and often operate the publication of PhD dissertations, such as the Landelijke Onderzoeksschool Taalkunde (LOT). These research schools could also play a role in organizing the disciplinary communities that cluster around journals and make choices to found new journals or cluster existing ones, and make financial contributions to them. They could even be involved in the governance of these journals.

In addition, disciplinary institutes could formally recognize editors involved in these journals to make this part of their duties. Right now, that is not the case: editing for a journal is tolerated but not encouraged, as the top currency of research outputs are peer-reviewed articles, and any type of community service is somewhat looked down upon and certainly not valorized. So what I am imagining here is sustainable funding for diamond journals that involves various permanent institutional revenue streams – coming from libraries, research schools, and in-kind contributions from individuals and their department – conditional on periodic, say three to five year, external evaluation. But what is really required is a change in perspective: journals are essential research infrastructure, and if we do not fund it, nobody will.

What do you expect from (big) publishers with a commercial for-profit publishing model, which already have started moving specific journals to non-APC (e.g. publishing as a service, or S2O). How can we ensure prices for commercial services are fair and will stay that way?

I think the only way to ensure that prices are fair is to ask for price transparency. This is something that I started to do with the Fair Open Access Alliance on a small scale in 2016, but of course that initiative has now been overtaken by the cOAlition S Price transparency initiative that will result in a Journal Comparison Service that will allow librarians to compare a breakdown of commercial publishers’ services and their prices. And indeed, library consortia negotiating read and publish deals should also ask for detailed price transparency: when libraries are paying up to 3,000-4,000 euros per article in these deals, and when prices can differ from one country to the next by about 1000 euros, library consortia should ask what that is based on. And the answer can no longer be that it is based on historic subscription spend: we should pay for publishing services alone, not for reading privileges.

I also think a well-organized European or even global Diamond Open Access community could help us gain insight into prices. If we take back academic publishing, and only use very specific publishing services, say copy-editing and typesetting, and open source platforms and submission systems, we can easily calculate ourselves what the cost of various publishing services is, and compare that to the services provided by commercial publishers.

We see an increase of open access (funder) mandates. We need to touch upon this, since you are also executive director of cOAlition S, the coalition behind Plan S. Could you say something about the ideas and work the coalition is doing to promote equality and inclusiveness in scholarly publishing?

cOAlition S is of course an alliance of funding agencies, and their remit is that of their funded researchers, not that of all researchers in the world. At the same time, the cOAlition is keen not to promote inequities. I think there are two initiatives that we have developed that transcend the narrow scope of our funded researchers and are promoting equality and inclusivity. Rights retention strategy: claiming a CC BY license on the Author Accepted Manuscript of an article in a subscription journal allows authors to deposit that article in a repository. This does not require the author to pay anything. The Diamond action plan: strengthening and aligning diamond open access journals that do not charge authors or readers.

But more is needed, and not only from cOAlition S. We would like to promote globally equitable pricing for services. That is each country and university contributes financially as a function of their means (for instance income, but also purchasing power). This is something library consortia should also take up: they should ask how the price they pay offsets the price charged to countries with lower purchasing power.

Still, we’re stuck in the traditional academic credit (and funding) cycle where prestigious journals and presses can stay dominant players and further commercialize the academic publishing sector because they also own and/or use elements of this cycle, which in a sense stalemate the much needed transformation of recognition and rewards structures based on impact factors, excellence, and prestige. It is one of the reasons why open access (especially full and non-APC) is lagging behind, at least in some disciplines. Often heard arguments are: it can’t be good, because there is no one taking care of the quality, it doesn’t have an Impact Factor (IF), so it can’t be of high-quality, etc. etc. What do you think of this? And what is needed in order to make sure full (non-APC) open access journals are taken equally into account in recognition and rewarding structures?

Well, first of all there is of course the illusion that the IF measures quality. It does not. As we know, it is a very flawed measure that is based on very questionable underpinnings. Those people who invoke the IF as a measure of quality would never apply methodologies used in determining the IF for their own research. And yes, we need to change the incentives and rewards system, cOAlition S is contributing to that via its principle 10 in which funders pledge not to take the publisher, the name of the journal, or purely quantitative metrics into account when selecting grant applications. Narrative CVs are now widely used among cOAlition S funders, also by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) which has been a Plan S signatory from the start. And clearly, also we need new quality-based metrics that do a better job of measuring the impact of an article and a researcher in a given community. That is also something that depends on the size of the community, and its validation practices. Validation is not always given through citations. We need to have a much better and fine-grained understanding of such mechanisms. And last but not least, editing a journal and reviewing for journals should be much better rewarded. We know that every article requires three reviews, so we should ask people for their review-to-publication ratios during annual reviews. That is a metric I could get behind as a journal editor.

When it comes to full open access journals we of course already have the Directory of Open Access journals (DOAJ) that is doing a great job in determining the quality (academic and technical) and the practices of open access journals. cOAlition S, for instance, only recognizes fully open access journals that are registered in DOAJ.

But still, there are many obstacles. For instance, so-called ‘official’ recognition as a proper journal in many countries still requires being registered in the Web of Science (WoS), which is owned by Clarivate. And in many countries, researchers can only publish in journals that are in WoS and that have an IF. So this leads to the crazy situation that if you want to attract authors from those countries, you need to have an IF, even if you know full well that the IF is a completely flawed metric, and also that if you flip a journal from a commercial publisher to open access, you need to wait for five years to get that recognition. While the old journal you left behind, which was taken over by a new community, still takes advantage of the hard work of the previous community for five years after they resigned. This is what happened to Lingua: only now is it becoming apparent in Google Scholar’s h5 index for instance that the journal’s papers in that journal are being cited much less than before the resignation of the editorial board in 2015.

What does ‘publishing with impact’ mean in practice?

Read more impact stories from researchers here: Utrecht University Library – impact stories

In 2008 Harvard’s Faculty of Arts & Sciences voted unanimously to adopt a ground-breaking open access policy. Since then, over 70 other institutions, including other Harvard faculties, Stanford and MIT, have adopted similar policies based on the Harvard model. In Europe such institutional policies have, so far, been slow to get off the ground.

We are beginning to see that situation change.

Birkbeck, University of London, has recently launched its new Open Research Policy, in line with its founder’s vision of opening access to research findings, outputs and outcomes. In the following interview, Paul Rigg, Senior Assistant Librarian (Repository & Digital Media Management) at Birkbeck, explains why and how this policy was developed and shares three tips for any other institution that might consider adopting a similar approach. Special thanks to Sarah Lee, Head of Research Strategy Support at Birkbeck, for her edits and suggestions in shaping this piece.

cOAlition S: Could you please, describe the author copyright policy you have adopted at Birkbeck, University of London?

Paul Rigg: The Open Access facets of Birkbeck’s new Open Research policy currently apply only to “short-form” publications; that is, a) peer-reviewed, original articles appearing in journals or online publishing platforms (including review articles) and b) peer-reviewed conference papers accepted by journals, conference proceedings with an ISSN, or online platforms publishing original work.

Where a publication is not accepted in a fully OA journal/platform which meets licensing and technical criteria or is participating in a Transformative Agreement, the College requires authors to retain certain rights to their work. This is so it can be shared via the Green open access route with no embargo, under a CC BY licence. The researcher must include the following statement in the funding acknowledgement section and in any letter or cover note accompanying the submission: ‘for the purposes of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission’.

cOAlition S: Why did the idea of adopting an institutional rights retention policy emerge?

Paul Rigg: In 1823, the College’s founder Dr George Birkbeck set out his vision: ‘now is the time for universal benefits of the blessings of knowledge’. That statement continues to underpin the mission and culture of the institution and will be one of the principal foci when we celebrate our bicentennial. Rights retention is a key element of our new Open Research Policy and having the policy in place before this anniversary is one of the ways we are re-energising our mission for the 21st Century.

One of the benefits of rights retention is the easing of the increasing “policy stack” in Open Access. With Plan S applying to UKRI- and Wellcome-funded authors, and REF rules to a broader swathe of researchers, the College felt that clarification and distillation were necessary to give a few clearly defined rules applying to as many people as possible.

We also want to show our solidarity with other UK Higher Education Institutions (HEIs); Birkbeck is at the forefront of open access through our diamond platform, the Open Library of the Humanities, and has long been part of a group carefully considering the implementation of a UK Scholarly Communications Licence (UKSCL). As “big deals” with publishers become unsustainable for many, Open Access is becoming increasingly important to enable researchers to read, and build on, the work of their peers. As a relatively small but mission-driven institution, Birkbeck is potentially in a better position to pivot than many larger HEIs.

As ‘big deals’ with publishers become unsustainable for many, Open Access is becoming increasingly important to enable researchers to read, and build on, the work of their peers.

cOAlition S: How was the agreement reached across the institution?

Paul Rigg: A data policy was being developed concurrently with a new open publications policy, so combining these into an overarching open research policy made sense. During the summer of 2021, a first draft was drawn up by members of our Open Research Working Group. Once general principles were ratified, the policy went through several drafts incorporating input from colleagues, including the repository manager, data manager, and other specialists. It was sent to the College’s Research Committee in October 2021, then Academic Board in November 2021, before being reviewed by our Governors. A more “dynamic” guidance document incorporating information from both Wellcome Trust and UKRI will accompany the policy.

cOAlition S: What challenges had to be overcome before it was agreed to adopt the policy?

Paul Rigg: There was concern in academic circles that this kind of policy effectively prevents publishing with some major publishers who will not tolerate rights retention. This is a legitimate concern but one we are working through with our academic colleagues as the situation evolves.

Our policy is an open research policy rather than specifically an open access policy, giving us an opportunity to further clarify aspects of data protection legislation and GDPR. Parts of the policy were rewritten to address participant data and confidentiality, with explicit reference to GDPR.

A future challenge is that by ensuring that the policy runs parallel to existing open access initiatives (Wellcome and UKRI), we will need to stay up to date on even minor alterations to those.

cOAlition S: What are the advantages of adopting the policy for your researchers and your institution?

Paul Rigg: The primary advantage is that open access gets our research out into the world; it enhances not just the visibility and reach of the college but of individual researchers. It enables better communication of ideas and easier collaboration as a means of exploring them. In short, it supports us to deliver our mission better. Rights retention specifically acknowledges not just the hard work but also the ownership of the expression of ideas by researchers.

The College hopes rights retention will help normalise deposit on BIROn (Birkbeck Institutional Research Online, the College’s institutional repository) without embargoes, thus smoothing compliance with UKRI and Wellcome policies, not to mention supporting planning for the next REF exercise.

Rights retention specifically acknowledges not just the hard work but also the ownership of the expression of ideas by researchers.

cOAlition S: In conclusion, what are your three top tips for any other university considering adopting a similar permissions-based Open Access policy to yours?

Paul Rigg: 1) Listen to concerns from your academics and take them seriously. Many of these can be context-specific, and academic buy-in is crucial to the evolution of publishing culture.

2) Provide a clear route for help and advice when things don’t go according to plan. Colleagues can contact named individuals who are collaborating across professional services and liaising with external sources at both funders and other HEIs. This network is helping to define and resolve some of the challenges arising from the roll-out of the new policy.

3) Acknowledge that we are all in a learning phase and that there will be bumps in the road. Approaches may be dependent on circumstances, so solutions are not always applicable across all contexts. Funders do not always seem to have satisfactory answers to questions which have not been asked before. Academics face unique challenges as many variables come into play on any given piece of work. We cannot yet see the horizon; at times, we cannot see a few metres ahead, but the ground is there, and we all have a role to play in shaping it.

More questions about Birkbeck’s Open Research Policy?

In 2008 Harvard’s Faculty of Arts & Sciences voted unanimously to adopt a ground-breaking open access policy. Since then, over 70 other institutions, including other Harvard faculties, Stanford and MIT, have adopted similar policies based on the Harvard model. In Europe such institutional policies have, so far, been slow to get off the ground.

We are beginning to see that situation change.

The University of Cambridge has recently established a pilot rights retention scheme on an opt-in basis, with a view to informing the next revision of the University’s Open Access policy. In the following interview, Niamh Tumelty, Head of Open Research Services at the University of Cambridge, describes the purpose of the pilot, how researchers can benefit from it and shares her tips for any other institution that might consider adopting a similar policy.

cOAlition S: Could you, please, describe the author copyright policy you have adopted at your university?

Niamh Tumelty: We are inviting researchers to participate in a Rights Retention Pilot, which will run for one year starting April 2022. Participating researchers will grant the University a non-exclusive licence to the accepted manuscripts of any articles submitted during the pilot, making it easier for us to support them in meeting their funder requirements by uploading their manuscripts to our institutional repository, Apollo, without needing to apply an embargo. The pilot has launched using a CC BY approach as required by most cOAlition S funders, and we are exploring providing an option for alternative licences for researchers who do not have that specific requirement.

The researcher will notify the journal by including the rights retention statement on submission. When the paper has been accepted, the researcher will upload the accepted manuscript as normal via Symplectic Elements, indicating during the upload process that they have retained their rights. The Open Access team will do their usual checks, advise the researcher on what will happen next and arrange for the article to be made available on Apollo.

We will closely monitor what happens during the pilot and all participating researchers will be able to comment on their experiences. We will review all feedback and use it to inform our next review of our institutional open access policy.

cOAlition S: Why did the idea of adopting an institutional rights retention policy emerge?

Niamh Tumelty: The introduction of the requirement for immediate open access to research supported by cOAlition S funders has proven challenging in practice, with some publishers offering no compliant publishing route and others charging unsustainable prices for immediate open access to the final published version. Unless researchers want to move exclusively to publishing in journals that are diamond, fully gold or included within read & publish agreements, they need a way to retain sufficient rights, so that they always have the option to post their accepted paper online to achieve open sharing of their scholarship. Some disciplines have been left with little or no choice about where they can publish their research while meeting their funder requirements and their own goals for open research.

The rights retention strategy is a key tool to enable researchers to openly publish in whatever journal will reach the most appropriate audience.

cOAlition S: How was consensus reached across the institution?

Niamh Tumelty: The fact that immediate OA is now a funder requirement for the majority of our researchers made the conversation relatively easy. We held a number of discussions at the Open Research Steering Committee to ensure that we had as full an understanding as possible, providing examples of issues that were arising in the first year of the Wellcome Trust rights retention requirement in the absence of an institutional policy.

We considered developing an institutional opt-out policy as others have done but concluded that the highly devolved nature of the University of Cambridge would have made it extremely difficult to conduct a thorough consultation and reach consensus by the deadline of 1 April 2022. We agreed that the most appropriate next step at Cambridge was to run a pilot on an opt-in basis. A working group was established to design this pilot and included researchers from across a range of disciplines along with open access and scholarly communication experts from Cambridge University Libraries. The working group met every two weeks from mid-January to the end of March to consider the issue from different disciplinary perspectives and to develop the approach for the pilot. We drew heavily on the policy that was introduced at the University of Edinburgh earlier this year, learning also from the UK Scholarly Communications Licence and Model Policy and recommendations that have been publicly shared by Harvard University. We brought the proposed pilot to the University’s Research Policy Committee for comment and took legal advice on the detail of how we would approach this before launching.

The beauty of a pilot approach is that no researcher has to participate – they have a choice about whether or not to opt in and will have the opportunity to influence whatever policy is ultimately introduced across the university. We can take this year to really understand the issues in detail and to build consensus about the best approach for Cambridge.

cOAlition S: What challenges had to be overcome before it was agreed to adopt the policy?

Niamh Tumelty: The biggest challenge in the lead up to the pilot has been understanding and developing confidence in the rights retention strategy. The expert legal advice we received following the announcement of the Wellcome Trust requirements and again as we designed the detail of our approach was critical in enabling us to develop the pilot. Now, our challenge is to clearly communicate and explain rights retention to our many researchers as a route they can choose when publishing and to grapple with any issues that arise during the pilot year before developing any full institutional policy.

cOAlition S: What are the advantages of adopting the policy for your researchers and your institution?

Niamh Tumelty: The rights retention strategy is a key tool to enable researchers to openly publish in whatever journal will reach the most appropriate audience. It may be that some publishers decide to reject any papers in which the author has retained their rights, but this seems an unsustainable position given the growing number of authors whose funders require immediate open access for all outputs.

The advantage of a pilot approach rather than a full institutional policy is that it provides space and time for deep engagement across our highly devolved university. It creates a framework for the researchers that wanted to have an early route to support them in retaining their rights and for the open access team that advises and supports them. It enables us to generate evidence from our own researchers, to build confidence and trust and to refine the approach ahead of shaping a full institutional policy.

Researchers are in a stronger position than they realise – if publishers want to continue getting this free content from our researchers, they will need to develop publishing routes that meet the needs of their academic communities.

cOAlition S: As a conclusion, what are your three top tips for any other university considering adopting a similar permissions-based Open Access policy to yours?

Niamh Tumelty: 1) Include a range of disciplinary perspectives from the earliest stages of planning. This early consideration will make it easier to tailor the messaging to different parts of the university, taking into account the different drivers and concerns that come into play. Make sure that the humanities perspective is included – too often in open research initiatives the humanities appear to be an afterthought, if considered at all.

2) Anticipate the questions that will be asked and make sure that you have clear and honest answers to those questions. Be honest and open about the fact that we are learning through the process (while building on the experiences of those who have gone before) and that there will be challenges. This enhances credibility and manages expectations as the policy beds in.

3) Have confidence in this approach! This is not new – researchers have been retaining their rights in this way for over a decade and it is becoming increasingly common practice across a range of institutions. Researchers are in a stronger position than they realise – if publishers want to continue getting this free content from our researchers, they will need to develop publishing routes that meet the needs of their academic communities.

Recommended listening

Research Pages: Rights Retention (podcast)

More questions about the Rights Retention Pilot? Contact the Open Access Team

In 2008 Harvard’s Faculty of Arts & Sciences voted unanimously to adopt a ground-breaking open access policy. Since then, over 70 other institutions, including other Harvard faculties, Stanford and MIT, have adopted similar policies based on the Harvard model. In Europe such institutional policies have, so far, been slow to get off the ground.

We are beginning to see that situation change.

The University of Edinburgh adopted its Research Publications & Copyright policy in 2021. In the following interview, Theo Andrew, Scholarly Communications Manager at the University of Edinburgh, explains how this policy was developed, describes the benefits for the University’s staff and shares his tips for any other institution that might consider adopting a similar policy.

cOAlition S: Could you, please, describe the author copyright policy you have adopted at your university?

Theo Andrew: The University of Edinburgh Research Publications & Copyright policy starts off by confirming that members of staff own the copyright to their academic publications in line with current custom and practice. Then, upon acceptance of publication each staff member agrees to grant the University of Edinburgh a non‐exclusive and irrevocable licence to make the accepted manuscript version of their scholarly articles publicly available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. It is important to note that this assignation of rights happens automatically and no effort is required by the author to fill in forms or add rights retention statements to journal submissions.

After granting the licence each staff member then agrees to provide an electronic copy of the accepted manuscript in an appropriate electronic format. This article will then be deposited in the Institutional Repository and made open access upon publication. This policy applies to all peer-reviewed research articles, published in either a journal, conference proceeding or publishing platform, authored or co-authored while the person is a staff member of the University of Edinburgh.

cOAlition S: Why did the idea of adopting an institutional copyright/rights retention policy emerge?

We started drafting the policy with the intention of clearing up the ambiguity of copyright ownership, and ended up aligning our University policy with the Research Funder vision of immediate open access.

Theo Andrew: The previous University of Edinburgh Research Publications policy was over 10 years old. Given the many recent changes in the open access policy landscape it was looking extremely out of date. We began thinking about updating our institutional policy around the time when the UK-Scholarly Communications Licence and Model Policy was being developed. This initiative inspired us to start drafting some wording based loosely on their Model Policy. When Plan S was initially announced in 2018 we were further encouraged by the 10 guiding principles. In particular we were inspired by the statement that the group of cOAlition S funders encourage universities to align their policies and practices with the Plan S principles of immediate open access and rights retention. So we started drafting the policy with the intention of clearing up the ambiguity of copyright ownership, and ended up aligning our University policy with the Research Funder vision of immediate open access.

cOAlition S: How was agreement reached across the institution?

Theo Andrew: To start proceedings with a solid footing we initially consulted the institutional Legal Services team who were able to give us confidence that what we were proposing was legally viable and that we had backing from the University. We then sought to brief the University’s Senior Management Team and seek their support to proceed. With this in place we were able to navigate the various academic committees that govern the University – including, but not limited to, various College and School Research Committees, Knowledge Strategy Group, HR Policy Development Group, Research Policy Group – before ending up at the University Executive for formal approval. The Policy is effective from January 2022, but with a public launch in April, to tie in with UKRI open access policy.

cOAlition S: What challenges had to be overcome before it was agreed to adopt the policy?

Theo Andrew: One of the major challenges for us was navigating the complex governance structure of a large and diverse research intensive university. Getting the time and attention to be included on committee agendas – where open access is not necessarily a primary concern – was helped enormously and encouraged by research funders joining initiatives like Plan S.

A secondary, but massive challenge we had to manage, were significant time delays that were introduced due to high impact/priority external factors like Covid-19, UCU strike action, and the REF2021 exercise. The cumulative effect was to add about a year on to our overall implementation time.

cOAlition S: What are the advantages of adopting the policy for your researchers and your institution?

Theo Andrew: There are a number of routes available for authors to make their work open access (APCs, self-archiving, Read & Publish deals, Diamond OA etc) and the policy fits in and complements these various options. It helps to level the playing field and offers the choice to authors who wish to self-archive and make their research immediately open who would normally be bound by restrictive embargo periods.

The policy also allows our institution the flexibility to immediately react to future policy changes; for example, the long-anticipated next REF exercise will likely contain immediate open access requirements. This policy ‘future proofing’ puts the institution in a really good position as we won’t have to make changes as we will be already compliant.

One of the less tangible, but powerfully important benefits for our researchers is that the policy is an affirmation from the University that the institution they are part of fully backs and supports them in their open access practices. All too often many researchers feel that they are stuck in the middle of a conflict between research funders and the journal publishers. With an institutional policy offering a route to immediate open access through self-archiving, the authors are not acting as individuals, but have the weight of their institution behind them which empowers them to act.

With an institutional policy offering a route to immediate open access through self-archiving, the authors are not acting as individuals, but have the weight of their institution behind them which empowers them to act.

cOAlition S: As a conclusion, what are your three top tips for any other university considering adopting a similar permissions-based Open Access policy to yours?

Theo Andrew: 1) Ask for help from other institutions who already have a policy in place. We couldn’t have developed our policy in isolation and have benefited greatly from discussions with other institutions. In turn we are more than happy to share our knowledge and experience and have done so with a dozen universities in the UK.

2) There will be unforeseen knockbacks along the way so it is important to develop resilience. Flexibility and persistence are fantastic attributes.

3) Familiarise yourself with the governance structure of your institution and build trusted relationships with key people before starting out. Once you have proved to stakeholders that you can be trusted to deliver change the whole process of developing and implementing policy becomes much easier.

Recommended reading

More questions? Contact the Scholarly Communications Team: Help & support